CalPERS, CalSTRS and other government

pensions

Pension reform allows cities to bypass bargaining

Posted on September 4, 2012

Pension reform approved by the Legislature last week gives many cities new

cost-cutting power that some have been unable to win from public employee unions

at the bargaining table.

The legislation does not cover several of the statefs biggest cities that

have independent retirement systems, some with well-publicized pension problems:

Los Angeles, San Diego and San Jose.

But for most cities the legislation extends retirement ages, caps pensions

and gives new hires a lower pension by imposing a single formula (rolling back

increases after SB 400) instead of allowing bargaining on a menu of different

formulas.

The legislation calls for a 50-50 split of gnormalh pension costs between

employers and employees. As current contracts expire, if unions do not agree to

equal cost sharing in bargaining by 2018, cities can impose an employee

contribution increase.

A survey of city managers earlier this year by the League of California

Cities found that 47 percent of the responding cities had bargained lower

pensions for new hires and 64 percent had bargained increased employee pension

contributions.

gWhile not perfect, the League views this legislation as a substantial step

forward in implementing pension reform largely in keeping with the Leaguefs own

comprehensive pension reform principles,h the League directors

said in a statement last week.

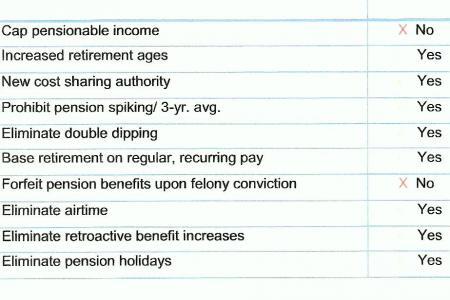

The League agrees with eight of the 10 points in the legislation, AB 304,

prepared in private by Democratic legislators and Gov. Brown. He asked that two

of his original 12 points be omitted for possible action later: retiree health

care and pension boards.

The cities dislike a cap on high-end pensions for new hires, preferring a

ghybridh plan with a pension providing at least 70 percent of final pay. And

cities think pension forfeitures should be limited to felonies for pension

fraud, not broader activities.

League of Cities policy aligns with eight of 10

reforms

The legislation limiting bargaining for pensions moves California closer to

the mainstream.

About 30 states allow collective bargaining by public employees. But only a

few allow bargaining for retirement benefits — notably California, Vermont and

New Jersey in a survey by the National Association of State Retirement

Administrators in 1998.

Critics say bargaining resulted in gbidding warsh that drove local government

pensions to unaffordable levels. New benchmarks were set when tCalPERS sponsored

SB 400 in 1999 giving state workers a major pension increase.

Three formulas for pensions, a ladder for step-by-step increases, were added

for local governments by AB 616 in 2001. Although not a sponsor of the bill,

CalPERS offered local governments an incentive for boosting pensions with the

new formulas.

The California Public Employees Retirement System said it would reward higher

benefits by inflating the value of the local governmentfs pension investment

fund, making it easier for the employer to pay for the more generous

pensions.

The pension formulas specify an employee contribution, usually 5 to 8 percent

of pay, that can be changed through bargaining. The employer contribution, often

at least twice what employees pay, is adjusted annually as pension fund levels

rise and fall.

During bargaining, many employers agree to pay part or all of the employee

contribution, sometimes in lieu of a pay increase. The practice is common enough

to have its own bureaucratic term, EPMC or gemployer paid member

contribution.h

The president of a pension reform group said AB 340, though an gimportant

step to reform,h should have had a ghybridh plan making employees share the risk

of investment losses and a constitutional safeguard against a rollback by future

Legislatures.

gThe provision requiring that almost all public sector employees pay half the

cost of their pensions is the most significant of the reforms and will provide

both immediate and long-term savings,h Marcia Fritz of the California Foundation

for Fiscal Responsibility said in a news release.

If employees increase their pension contribution, employers can reduce their

contributions by a similar amount

Prodded by a record 100-day state budget deadlock, the largest state worker

union agreed two years ago to raise employee contributions from 5 to 8 percent

of pay, helping to reduce the annual state payment to CalPERS by about $400

million a year.

On the other hand, the city of Sacramento

laid off 16 police officers in July because the police union would not

begin paying the employee share, 9 percent of pay. Sacramento firefighters

agreed to phase in full payment of their employee contribution.

AB 304 calls for an equal employer-employee split of the gnormal costh for

pensions earned during the current year. But most retirement systems have an

gunfunded liabilityh from shortfalls in previous years caused by below-target

investment earnings.

For example, last year state miscellaneous workers contributed 8 percent of

pay, more than half the 14.4 percent normal cost. But state employers

contributed 18.2 percent, an amount that includes a payment for a large unfunded

liability.

In a review of the governorfs plan last November, the nonpartisan Legislative

Analystfs Office said employees should share in the cost of the unfunded

liability, but doubted that higher employee contributions can be legally imposed

on many workers.

gSince increasing current employeesf contributions is one of the only ways to

substantially decrease employer pension costs in the short run, the legal and

practical challenges that we describe mean that the governorfs plan may fail in

its goal to deliver noticeable short-term cost savings for many employers,h

said

the analyst.

The legislation apparently is designed to clear legal hurdles by changing

bargaining law to give employers more flexibility to increase employee

contributions. Impasse procedures can be used to impose contribution

increases.

A legislative analysis of AB 340 said impasse cannot be used for contribution

increases that exceed statutorily required contributions for current employees

or half the normal cost for employees hired on or after Jan. 31, 2013.

Local governments have until 2018 to bargain employee contributions that

share half of the normal cost. Then imposed increases are limited: 8 percent of

pay for miscellaneous workers, 12 percent of pay for police and

firefighters.

Importantly, the self-described guardian of pension gvestedh rights under

contract law, CalPERS, is not warning that requiring employees to pay half the

normal cost is likely to be challenged in court.

A CalPERS analysis

said only two parts of the plan may raise vested rights issues: barring

current employees from purchasing gair timeh service credits to boost their

pensions, and requiring some members convicted of felonies to forfeit their

pensions.

Narrowing an earlier preliminary estimate, CalPERS told legislators the

legislation should save employers using its plans between $42 billion to $55

billion over the next 30 years.